Samuel Washington Allen Prize Honorable Mention, selected by Robert Pinsky

Add One Father to Earth

I.

Shelved where his shoes had been,

his unrested ashes waited in a black lidded box

in stout plastic held close in his vacant clothes closet

above the hamper where I threw the garments

he wore to ride in his final ambulance.

After sixteen weeks I carried them through the Florida city.

At the airport they were scanned with a smile for explosives.

In Massachusetts his ashes rode with us

past a weed-ridden car dealership.

No one but me remembers

the small-town lunch spot in that place. We scavenged

our first nothing-open-Sunday sandwiches there.

One last trip past that obliterated memory

on the way to the church of dwindling

recollections, church for thirty years before

my parents’ migration toward lawn egrets and ditches

for stormwater. Returned back from Paradise

to the church where my father troweled

my mother’s remains seven years before.

Where we then committed his. So much human grit.

Seventeen people stooped to the earth.

Now it settles in earth, uncoffined,

unmarked, fluid as matter through matter.

A remnant preserved for my desk

in a modest marble urn, before me

on a blue October with its stubborn

city greenness of trees.

II.

He lifted his free right arm

from beneath his hospital blanket.

Forced speechless by the apparatus

propelling his lungs, he opened his hand

toward us. His fingers curved one by one

in a cascade against his palm, little finger

rippling toward index finger.

He did this three times. We saw it,

the gentle opening and graceful closing

of his grip. We didn’t understand.

He then spread his palm to face us, moved it

side to side in-towards and out-away from him.

This we understood, because as children

we learned to wave when it was time

to go from someone.

But first, he spread and curled his fingers

to grasp no one’s offered hand.

I saw this and I blanked.

When I first held

the density of his remains, I realized

what he had asked of us.

I knew it only then.

III.

Sixteen weeks’ stillness on his closet shelf,

the closet in service to their bedroom.

Waking one morning, he told my mother he couldn’t

do it anymore, could not, could no longer

lift her, walk her, feed her.

A nursing home opened to her before sundown.

Sixteen weeks sacked

in resolute plastic necked by a dog tag

in a snap-brim box in a floral yellow shopping bag

of sympathy.

IV.

Famished family lost without lunch

in our new little town. Sunday noon

in 1963, Lord’s-Day-we’re-closed. Nothing

in the cupboard. The movers left us.

We’d hauled our trek from corn country Indiana

to tobacco shed Massachusetts,

the best asparagus earth on earth.

The Gronostalski onion truck, prodigious

Polish name festooned wide in paint

fading even then. Stan the Vegetable Man

whose beacon sign blazoned a man

figured, yes, of vegetables.

These decaying stalwarts still held the roadside

fifty years later, wayposts for homecomers.

But brand new then, still lunchless,

we roamed Route 9 in the red Rambler,

three cranky boys, two disoriented parents.

Who could tell how this little lunch place arose

like a vision, the Spruce Hill Restaurant,

a Brigadoon of sandwiches.

That eatery of the first day of the rest of our lives.

At some erased moment between then and now

the slope-roofed lunch box poked its sides out,

glassed its front to sell autos. Failed quickly.

There are its stubborn barren windows, shameless stains,

opportunist weeds: souvenir I remember and reject.

Something of my father goes for his final ride

past our first meal. And I want to challenge

someone: find the strength to take

this forsaken hulk, render it to atoms, lay it down.

V.

Grit the color of faint afterfeathers

in an equable porcelain bowl

set near dug-out earth.

A car radio edges the church sidewalk

beyond the garden. The thought

of entertainment by subwoofer serenade

frets me. And there is a lot of ash.

Four sons, two wives, two girlfriends, grandson,

each settles a ceremonial scoopful

in the empty space. Still there is much ash.

I call to the witnesses, make impromptu

community event of this. Four cousins,

two husbands, put their hands to the work.

Sister-in-law’s father and stepmother take it up.

Each in stillness with their minds arcing

toward the trowel, its mass.

Christ, there is so much ash left.

I squat, take the bowl at the lip,

empty his persisting remains

directly into the gape

like cups of flour into a mixing bowl.

I don’t want that image.

But maybe it is that image.

Add one father to earth.

Cover and let stand overnight.

Let stand permanently.

VI.

Let stand permanently,

that tablespoon-worth of him saved

before passage through the airport,

before passing the first-lunch ruin,

before the memorial garden.

Saved for a desktop urn, veined

in lightning bolts of rust-red with patches

of near-white like elderly skin.

Marble monument cool

against my palm, fingers wrap

like tendrils around the jar.

Fragment or fractal of the gravestone

he refused with adamance.

He would not be left as a site

of pilgrimage, a chiseled name

filled over time with lichen, a site

of contrite visits, first rare, then none.

Instead, he is at home with me

while my home persists,

before me in the shifting

late October sun. I close my eyes

against the waxing daylight,

open them upon his urn again

in the temporary darkness.

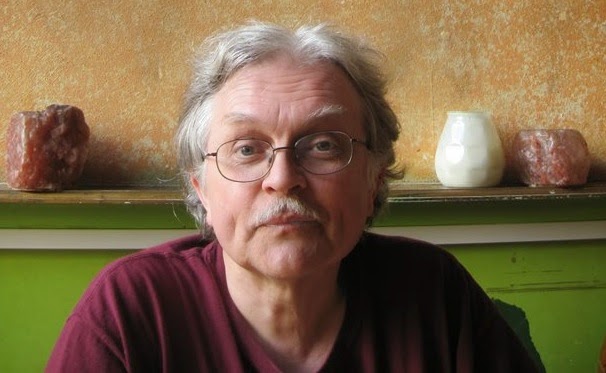

David P. Miller’s poems have recently appeared in Meat for Tea, Hawaii Pacific Review, Turtle Island Quarterly, Nixes Mate Review, The Lily Poetry Review, and What Rough Beast, among others. With a background in experimental theater before turning to poetry, David was a member of the multidisciplinary Mobius Artists Group of Boston for 25 years.